Body of IITR

Recently, a study by researchers at the Department of Architecture & Planning, IIT Roorkee explored Solid Waste Management at university campuses as a model for larger cities. They use IIT R as a case study and propose methods to work towards achieving a zero-waste campus. Watch Out! attempts to summarize their observations.

Have you ever wondered what happens to the food that you slide from your plate into the dustbin in the mess? Or the chai cup that you take from the canteen at 2 am? The autumn leaves scattered on the road, crunching beneath your feet?

They go into the dustbin, obviously. Then where? A bigger dustbin? Um. Probably. And then?

This is where Solid Waste Management (SWM) comes into the picture.

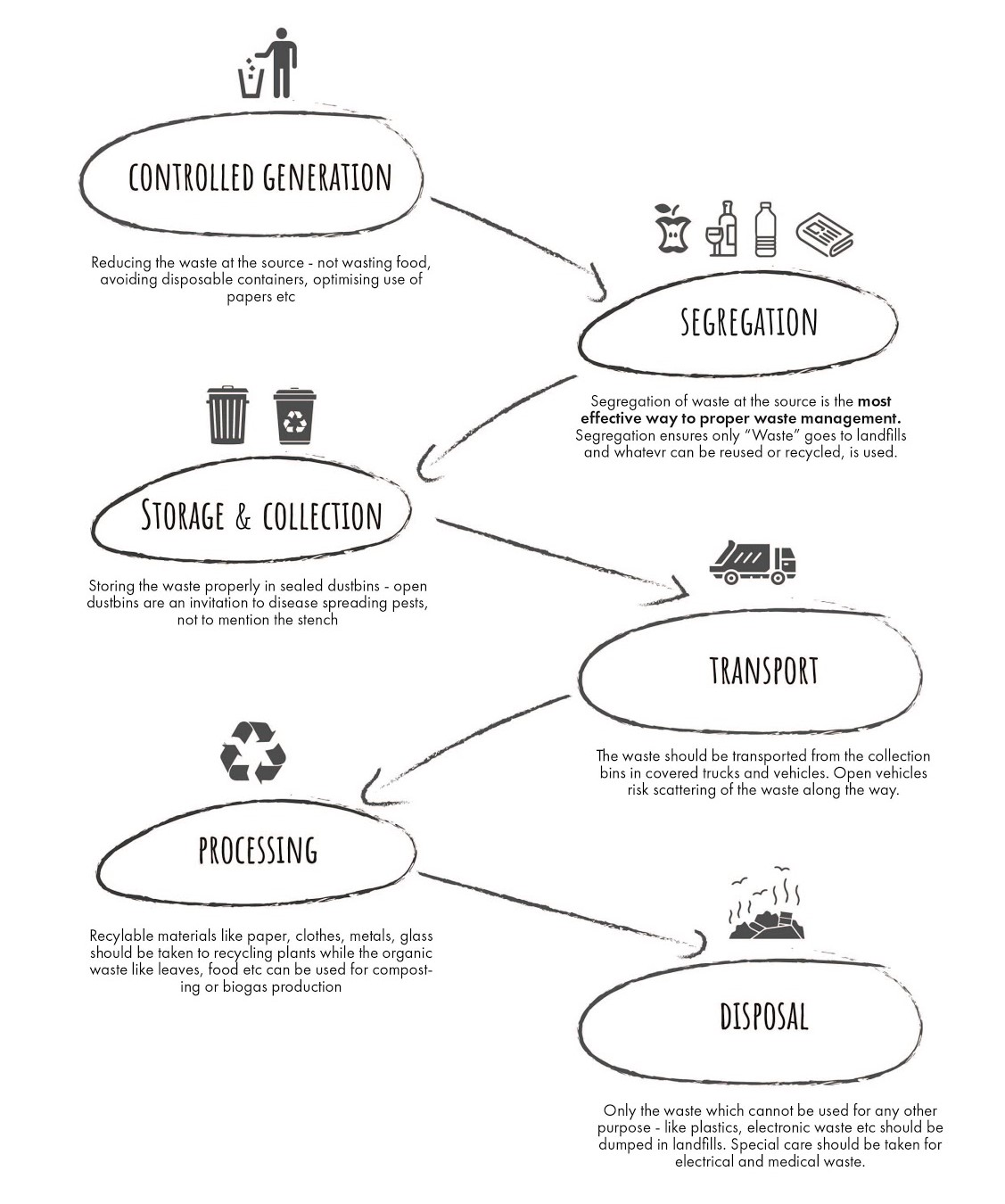

Solid Waste Management deals with the entire life cycle of waste from generation to disposal. SWM must account for external factors such as public health, economics, and environmental conditions. The main objectives of SWM are to achieve this while maintaining hygiene standards and reducing the quantity of solid waste left over after the recovery of material and energy.

Solid Waste Management deals with the entire life cycle of waste from generation to disposal. SWM must account for external factors such as public health, economics, and environmental conditions. The main objectives of SWM are to achieve this while maintaining hygiene standards and reducing the quantity of solid waste left over after the recovery of material and energy.

With rapid population growth and urbanisation, annual waste generation is expected to increase to an average of 381 kg per person per year.

Poorly managed waste is contaminating the world’s oceans, clogging drains and causing flooding, transmitting diseases via breeding of vectors, increasing respiratory problems through airborne particles from burning of waste, harming animals that consume waste unknowingly, and affecting economic development such as through diminished tourism, not to mention the rapid depletion of open lands due to dumping of waste.

For a long time, developed nations transported their untreated wastes to underdeveloped nations for disposal, since the cost of treating waste was lower than transporting and dumping where land was available. Even now, within countries - the waste of the cities tends to be dumped outside the city perimeters into the outskirts, leading to littering in areas where there are not sufficient methods of waste treatment.

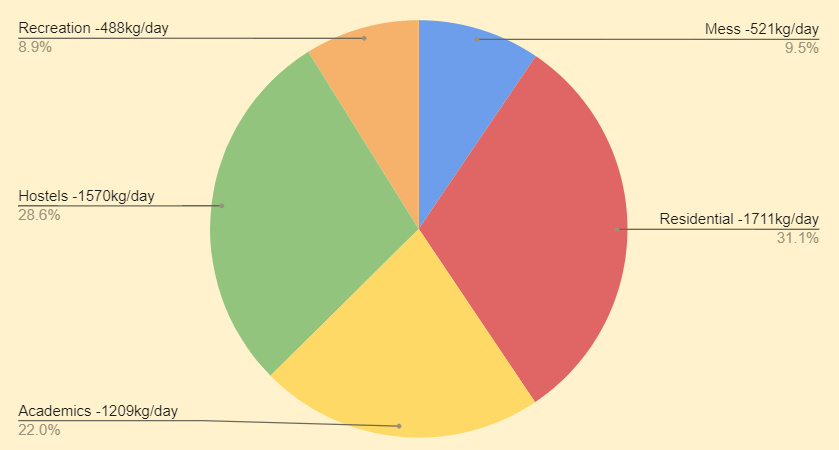

Universities like IIT Roorkee can today be regarded as ‘small cities’ due to their large size, population, and the various complex activities taking place on campus. IIT Roorkee covers an area of 356 acres, has around 12,000 residents and has residences, eateries, academic and research facilities.

IITR produces five-and-a-half tonnes of waste every day.

All this waste is processed locally. The waste generated within the campus is collected from the community bins twice a week by a local contractor. It is transported to and dumped at the municipal disposal site. Only the faculty and staff residences have colour-coded bins for segregation of waste at the source.

Waste collectors and local-vendors (kabadiwalas) collect waste like glass bottles, newspapers, metal scrap, etc. from residences of staff and hostels. NSS also carries out services to collect old used clothes and distribute among the needy.

A dedicated SWM program on the campus will make campus occupants aware of waste management. It will increase the productivity of students and employees by providing a clean and healthy workplace. SWM also influences the local community economically as well as environmentally.

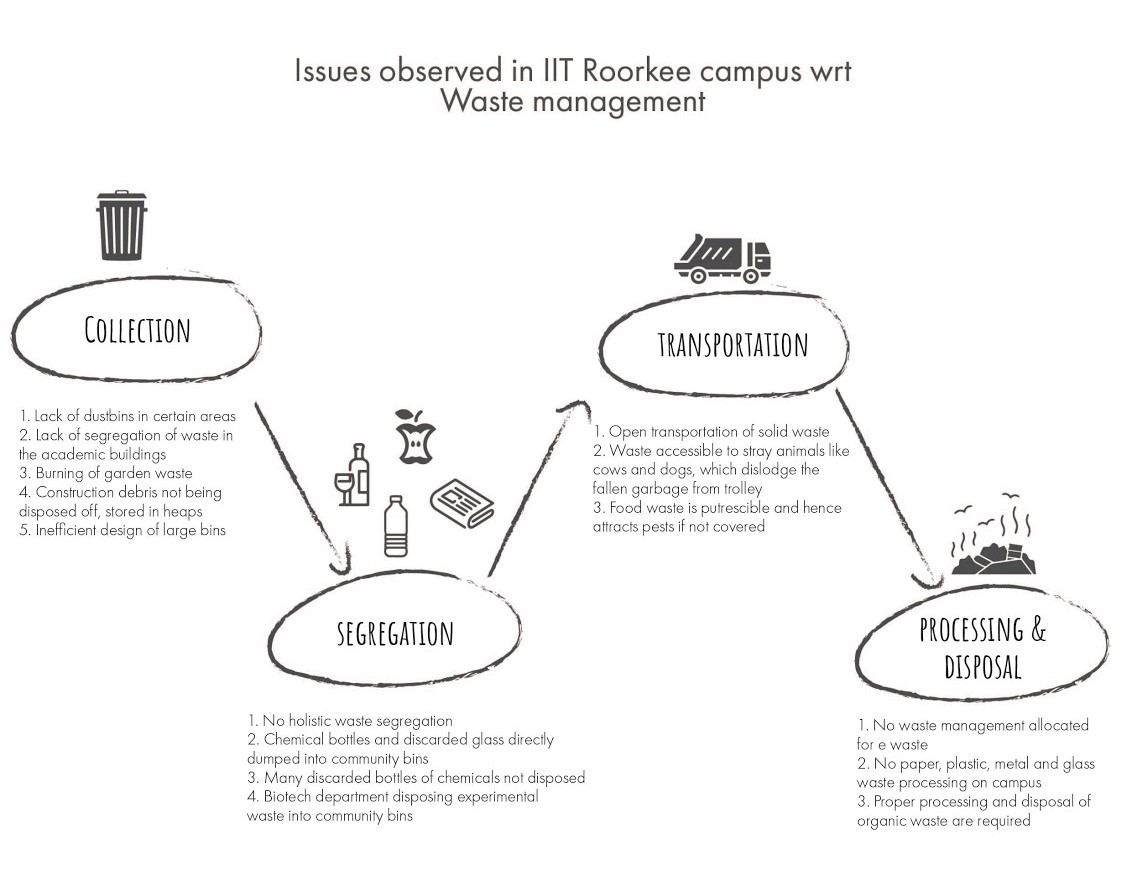

The following issues have been documented.

“Zero Organic Waste” here means minimising (ideally eliminating) the organic waste to be collected and dumped in landfills from the campus. Most of the waste generated on campus is organic and compostable. However, due to the lack of proper SWM techniques, most of this “usable” waste ends up in landfills.

Reducing waste at the prime source is the first step of the waste hierarchy and coping mechanism. Awareness is essential for the success of any further developments. Conduction of workshops and competitions provide an added benefit of generating new solutions.

Policies such as segregation of waste at the source allow different types of waste to be processed independently. This makes the system more efficient as a major fraction of segregated waste is recyclable or suitable for incineration. The recent installation of colour-coded bins at Rajendra Bhawan and e-waste bins across the campus are a step in this direction.

Organic waste shredders make food waste, green vegetables, bones, garden waste etc easier to process. Biomechanical Composters convert organic waste added to the machine into nitrogen-rich compost by reducing its volume by almost 70–80% of the original. Organic waste can also be used in the generation of house biogas which can be used locally and externally.

Recently, Dr Ramesh Pokhriyal Nishank inaugurated a sewage treatment plant on the IITR campus. Separate waste trucks have been contracted to collect the waste from the collection sites. The institute also has a rotary dump composter which has not been of much use due to the lack of segregation at source. However, given the instalment of the bins, it is hoped the composter will be made use of.

On a campus the size of IIT R, waste management directly impacts our lives but often escapes our notice. Recently introduced policies and the establishment of an Eco Group and Institute Green Committee are a step forward. We can only wait and observe the results.